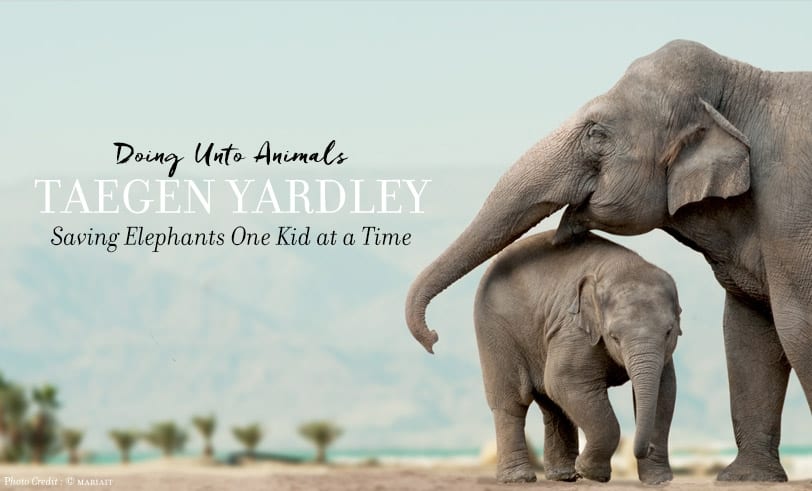

Doing Unto Animals: Taegen Yardley

– By Laurel Neme

Saving Elephants one Kid at a Time

As a writer, I’ve met children from Hong Kong to Vermont who are transforming attitudes about elephant ivory through a series of small actions. In Hong Kong, the “elephant angels”—three young girls, Nellie Shute, Lucy Skrine and Christina Seigrist (then ages 12, 11 and 9) started a petition to stop the selling of ivory at local shops because it led to the killing of elephants. Through their work, the shops decided to stop selling ivory, which in turn prompted the government to consider a wider domestic ban on commercial ivory sales.

In the United States, 12-year-old Taegen Yardley is also making waves. Now a seventh-grader in Charlotte, Vermont, Taegen first learned about elephant poaching three years ago from an October 2012 National Geographic magazine cover story on “Blood Ivory.” The scale of killing horrified her. About 30,000 elephants are poached each year for their ivory. Much of that goes to China and elsewhere in Asia for carvings, jewelry, and trinkets, but demand in the United States is also significant. Some say the United States is the second-largest market for ivory in the world.

When the National Geographic documentary “Battle for the Elephants” was shown at the University of Vermont in October 2013, Taegen and her friends held a bake sale to raise money for the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, a Kenyan-based organization that rescues and rehabilitates orphaned elephants. The children quickly discovered that each treat did more than fill the stomachs of filmgoers. The elephant-decorated cupcakes and cookies started conversations. As the children explained why they wanted to help elephants, their enthusiasm ignited passions in others.

But Taegen didn’t stop there. The movie touched her deeply. She spent hours reading and educating herself on elephants and their importance in the ecosystem. “I discovered what a large role elephants play in protecting our planet from climate change,” she explains. “The rain forests in Central Africa are one of our most important resources in fighting climate change. Elephants spread seeds throughout the land, which help new plants and trees to grow. They also open woodlands and clearings as they feed and roam, which creates more space for trees and plants to grow and helps to regenerate forests.”

“Elephants are living creatures, and so are we,” she says. “Instead of going out and killing such beautiful animals for their tusks, why can’t we just help them?”

TAKING IT TO THE LAW

Taegen got her chance again in spring 2015, when the Vermont legislature first considered a bill to ban the commercial sales of ivory in the state. While federal laws restrict both the importation of ivory and sales between states, they contain loopholes that allow both the sale of certain types of ivory, such as antiques, and intra-state sales. These exemptions let illegal ivory slip into the legal market.

Many states are considering bills to close this regulatory gap.

Two states, New Jersey and New York, passed such legislation in 2014, while at least seven others currently have bills on the table. Taegen hoped Vermont would be the first to pass ivory legislation in 2015. When Vermont’s House Committee on Fish, Wildlife & Water Resources held its first hearing on the bill (H.297) on April 8, she testified. Taegen sat alone at a small table as seven of the committee members, seated in a horseshoe around her, listened and asked questions.

“I will never be able to see an African Western Black Rhino. They officially became extinct in 2011,” Taegen said. “I don’t ever want to be able to say the same about elephants.”

“What can we learn from them?” one legislator asked.

“Elephants are very smart creatures,” Taegen responded. “They care about everybody and everything. Now that people are becoming threats to them, it’s harder for them to be friends with humans.”

Jon Fishman, drummer for the rock band Phish, spoke after Taegen. He became the first well-known musician to testify at a state hearing in support of an ivory sales ban. He did so at the urging of his children, who went to Endeavour Middle School with Taegen and shared her passion.

While the bill stalled in committee, it will be considered again in January 2016 when the legislature returns from break.

A MARCH FOR ELEPHANTS

Taegen continues learning and educating others. And her influence ripples through the community. In May, she gathered ten students from three different schools for a Skype call with ten similar-aged students from Clearwater Bay School in Hong Kong who had been actively petitioning their own government to stop ivory sales. During the 90-minute video call, the children shared their experiences and brainstormed ideas for future actions.

One of those ideas was a march for elephants. The Hong Kong students used a march for elephants to educate the public about ivory and build support to stop domestic sales. Taegen thought she could do the same. Vermont’s first march for elephants is scheduled for October 4, 2015 in Burlington, the state’s largest city. It’s now part of a Global March for Elephants that involves over 130 cities around the world (including 55 in the United States).

Taegen has already liaised with 14 other schools and is planning several kids’ art events. Children will gather several times in September to paint elephant-related t-shirts, banners, and signs. They also plan to build 96 pairs of paper maché tusks (192 in all), which the children will carry for the march and pile up at the end to represent the 96 elephants killed each day in Africa.

Taegen shows how everyone has the power to influence the world around them. By sharing a report at school, sending a letter to newspapers, or discussing an issue with family and friends, simple actions by young people can have a big impact.

Make a Paper Mache Elephant Tusk!

Are you planning on participating in the March for Elephants this year? Taegen is showing us how to make our own paper maché elephant tusks to carry with us as we march.

WHAT YOU NEED:

- utility knife

- wire cutter

- scissors

- pool noodles (one 4 ft noodle makes 4 tusks)

- wire

- duct tape

- plaster cloth

- tub/bowl warm water

- paper towels or newspaper

- recommended – plastic or newspaper to cover tables

1. CUT pool noodle lengthwise with utility knife.

2. CUT each half piece in half. You should now have four, two foot pieces.

3. CUT one 6″ piece of wire.

4. INSERT the wire into the inside of the noodle on one end.

5. SECURE with duct tape

6. TAPE one end of the noodle into a point.

7. USE newspaper or paper towel to FILL the center of the noodle and tape down. Make a slight bend in the tusk.

8. CUT strips of plaster paper (approx. 2 x 8).

9. DIP strips into warm water and COVER the noodle. Be careful not to wrap strips in the same direction. The tusk will be smoother and stronger if you wrap in different directions. Don’t let water drip on plaster strips prior to soaking them. This will cause them to harden and you will not be able to apply them.

10. ADD a bit more bend to the tusk once completed.

11. Allow to DRY for 24 hours.

* Each tusk takes under 10 minutes to make